THE UILENSPIEGEL SAGA

As my paternal grandmother, Adrienne Vantorre, was spending the weekend, lunch was somewhat delayed at our house on Saturday October 13th 1962. That also meant that my customary quick dial through the Medium Wave was a bit later than usual. But, around 14.25 hrs it happened to be just in time to hear Belgium’s first offshore station go on the air. Reception was very strong as the Uilenspiegel, a vessel made out of concrete, was anchored off Zeebrugge, where I lived and still do.

A different music era had just started -not on account of the new radio station- but because just a week earlier the Beatles had released ‘Love me do’, their first single for EMI. However, less than a fortnight later the world was in the grip of the Cuban missile crises. With the threat of nuclear holocaust hanging over us, we racked our brains over some sort of protection. With Uilenspiegel providing some entertainment in the background my father and I set to work in the back yard. The underground rainwater storage tank in reinforced concrete was blocked, drained and dried out, to serve as a makeshift fallout shelter for my mother and me. My father was sure he would be at sea should the Third World War kick off. Luckily we never had to make use of the dark and spooky underground chamber.

TAUNTING

AUTHORITY

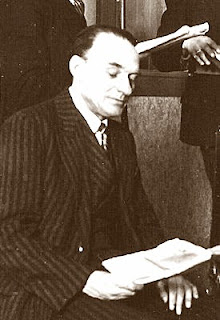

Uilenspiegel was the initiative of 73-year old Georges De Caluwé, from Edegem near Antwerp. In the previous months he had purchased the 585-ton supply boat ‘Crocodile’ in the French port of Brest. Well before the war, the vessel in reinforced concrete, had been cast in a mould, like a few of its sister ships. During the Summer of 1962 transmitting equipment was installed on board the vessel in Antwerp. It was subsequently towed to sea, having been aptly renamed ‘Uilenspiegel’ after a legendary sixteenth-century Flemish folk hero who was famous for taunting authority. The vessel was anchored at 51° 28’ North, 3° 12 East. The station announced itself as “Radio Antwerpen van op het schip Uilenspiegel op de Noordzee”, but everyone simply called it Radio Uilenspiegel. Station identification was accompanied by music from ‘Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks’, a tone poem by Richard Strauss. It is a lilting melody that reaches a peak, falls downward, and ends in three long, loud notes, each progressively lower. Broadcasts from Uilenspiegel were on 1492 kHz (201m), a frequency chosen because it was very close to the channel used by the transmissions for Antwerp by Belgium’s state-run regional radio. Apart from a half hour programme ‘Y’a de la musique’ at 16.30 in French, all other programmes were in Flemish and pre-recorded on land. In all 18 people were employed

With Uilenspiegel Georges De Caluwé got his own back on the Belgian authorities. After the war the Pierlot government, returning from exile in London and clearly suffering from Goebbels-syndrome, had refused to renew the licences of all independent broadcasters in the country. Since 1922 and until the Nazi invasion De Caluwé had been running a small commercial station. People called it ‘Radio Kerkske’, since the aerial had been erected on the tower of the Protestant church in Edegem. In the face of the intransigence of the Belgian government De Caluwé had sworn to get his station back on the air, even if it meant swapping a church for a ship of cement.

POPULAR,

PROUD AND LEGAL

It

was the succes of Veronica and Scandinavian stations such as Radio

Mercur and Radio Syd that had inspired Georges De Caluwé. In spite

of his age he regularly made the 6 mile dash to Uilenspiegel’s

anchorage to check on the equipment. Whenever the former

shrimper, called ‘Nele’, after the spouse of legendary Tijl

Uilenspiegel, took De Caluwé out to the ship, he invariably

went live on air for a few minutes around 12.25 hrs near the end of

the programme "Groeten van Uilenspiegel". In

his chat he reported on any improvements that had been carried

out on board. One Saturday he announced that the station could now

also be heard on 7.600 kHz in the 41 m band shortwave. He called it

an exciting moment and just days later reception reports were

received from as far away as Canada.

In

the evening the medium wave transmission could be picked up in large

parts of Europe. Georges De Caluwé explained to a Swedish journalist

that in the first few weeks of broadcasting he had received over a

thousand letters in the station’s post office box in Zeebrugge.

Apart from Belgium reception reports were mainly sent in from

The Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian

countries. During the day however reception on 1492 kHz was often

troublesome in parts of Brussels and Antwerp. To improve coverage a

move to a more favourable frequency was being considered, but this

never materialised.

De

Caluwé also stressed that he was “proud of the legality of his

station”. The ship was registered in Panama, and every month he

paid any copyright dues to Sabam, the Belgian performing rights

society. Furthermore all provisions and tapes that went out to the

vessel from Zeebrugge and occasionally Blankenberge were checked by

Customs and were given an export license.

MIDNIGHT

CLOSEDOWN BATTLE

Programmes

on the Uilenspiegel commenced every morning at seven with traditional

Westminster chimes. Apart from a wide selection of pop hits, also

opera, operettas and some classical music could be heard on the

station. The transmitting day ended at midnight. From the start

Uilenspiegel had been a thorn in the side of Belgian national radio,

but it was especially this late closedown which presented the state

broadcaster with a pretty problem. In those days shut down time for

the NIR was at 23.17 hrs. For years any later programming had been

blocked by the unions. They argued that announcers and technicians

working at the Flageyplein broadcasting house in the Brussels suburb

of Elsene had to be able to catch the last bus home. Hence the most

curious closedown time. However, just a week after Uilenspiegel

appeared on the scene, national radio also stayed on the air

until midnight. The unions had relented. How did the announcers and

technicians get home? Well, they used their cars, as they had always

done.

JUST

66 DAYS AT SEA

In

charge of programming for Uilenspiegel was Piet Jager.

Among the presenters Louis Samoy, Fred Steyn, who later joined

the Dutch /Flemish crew of Radio Luxemburg and Jos Jansen, who

became a journalist for national television in Belgium. I

remember the first breakfast programme on Uilenspiegel. It

was Sunday morning, October 14th

1962. I got up before the crack of dawn to hear the station go on the

air. The programme was pre-recorded and nerves clearly had gotten the

better of Piet Jager. He repeatedly gave the wrong time-check. When

he realised this, Jager excused himself profusely and promised that

such a mistake would never happen again on the station (“we zullen

het nooit meer doen”).

Also,

whenever I hear the sixties golden oldie ‘Chariot’ -the original

version of ‘I Will Follow Him’- it makes me think back to the

Uilenspiegel days. It was Petula Clark’s popular French song that

topped the pirate’s hit parade for most of its offshore existence.

In the event the vessel only remained a total of 66 days at sea, and

even less on air.

DEFEAT

FOR THE SHIP OF CONCRETE

The ultimate run of bad luck for the Uilenspiegel organisation started on December 13th 1962, with the death of its founder Georges De Caluwé after an operation at the Stuyvenberg hospital in Antwerp. Just two days later disaster struck again. The night of Saturday December 15th proved to be a devilish one for all shipping in the North Sea. A westerly force 10 to 11 gale came raging up The Channel battering sea-defences and pounding even the largest of vessels into submission. Near the island of Texel the coal-carrier Nautilus went down with the loss of 23 lives. Only one seaman was rescued after 5 hours in the water. Off Zeebrugge also the Uilenspiegel was doomed.

Around a quarter past three in the morning on Sunday, although firmly secured, one of the hatches gave way under the relentless onslaught of mountainous waves. The two crew members on watch sounded the alarm, as seawater came rushing into the ship. The generator failed and all electricity was lost. In the hold, the shortwave transmitter toppled over and smashed into the 10 kWatt medium wave. The Uilenspiegel was also dragging her anchor. On deck, by means of flares and setting fire to some clothing, the crew managed to draw the attention of the ‘Suffolk Ferry’. In spite of the severe gale, the train-ferry was on its daily run from Zeebrugge to Harwich. Subsequently the maritime station Ostend Radio broadcast this message on the emergency frequencies: “Following received from train ferry 'Suffolk Ferry': ‘Radio vessel moored six miles NE by N from Môle end, Zeebrugge is in need of assistance'. Two minutes later the Suffolk Ferry sent out an SOS: “Radio station is sinking and requires lifeboat assistance”. Immediately a rescue boat and the tug ‘Burgemeester Van Damme’ were scrambled from Zeebrugge and sent out to the stricken vessel. Until their arrival the train-ferry remained alongside sheltering the Uilenspiegel from the worst of the waves.

Around a quarter past three in the morning on Sunday, although firmly secured, one of the hatches gave way under the relentless onslaught of mountainous waves. The two crew members on watch sounded the alarm, as seawater came rushing into the ship. The generator failed and all electricity was lost. In the hold, the shortwave transmitter toppled over and smashed into the 10 kWatt medium wave. The Uilenspiegel was also dragging her anchor. On deck, by means of flares and setting fire to some clothing, the crew managed to draw the attention of the ‘Suffolk Ferry’. In spite of the severe gale, the train-ferry was on its daily run from Zeebrugge to Harwich. Subsequently the maritime station Ostend Radio broadcast this message on the emergency frequencies: “Following received from train ferry 'Suffolk Ferry': ‘Radio vessel moored six miles NE by N from Môle end, Zeebrugge is in need of assistance'. Two minutes later the Suffolk Ferry sent out an SOS: “Radio station is sinking and requires lifeboat assistance”. Immediately a rescue boat and the tug ‘Burgemeester Van Damme’ were scrambled from Zeebrugge and sent out to the stricken vessel. Until their arrival the train-ferry remained alongside sheltering the Uilenspiegel from the worst of the waves.

During the rescue effort 38-year old Oscar Vantournhout fell whilst leaping across to the Uilenspiegel. Seconds later he was crushed between the lifeboat and the drifting radio ship. Vantournhout was the owner of the local fishing vessel Z 63 and had taken the place of another lifeboat man who was unavailable. A week later Oscar Vantournhout succumbed to his injuries in hospital at the seaside resort of Knokke, leaving a wife and two young sons of just 12 and 7 years old.

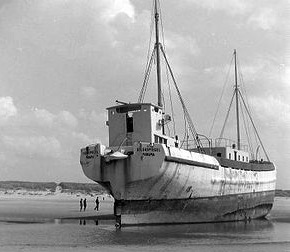

STRANDED

Three times in succession a tugboat tried to secure a hawser to the Uilenspiegel in an attempt to haul the vessel to safety in Vlissingen. Each time the towing cable snapped. Braving the atrocious weather many hundreds of people watched the vessel’s death throes from the seafront in Heist and Knokke. In the course of the afternoon the Zeebrugge lifeboat managed to rescue five of the nine crew members. The remaining four were taken off by the Dutch lifeboat ‘President Wierdsma’ and brought to the port of Breskens.

The 37-year old captain of the Uilenspiegel, local man Marcel Van Massenhoven from the coastal town of Heist, had refused to leave his ship. But when the push of a large wave brought him within arm’s length of the rescuers, they dragged him off. Only minutes later the concrete hulk swept past the Zwin estuary, and stranded on the beach at Retranchement, just a few hundred yards across the border in The Netherlands.

COFFEE

ANYONE?

The next few days many thousands came to watch the broken vessel on the beach. The more adventurous went souvenir hunting on board. For newspapers and even archenemy Belgian radio and television the demise of the Uilenspiegel became a major story. A string of journalists trooped off to the windswept beach of Retranchement to interview the people that came on a veritable pilgrimage to their lost radio station. Upon leaving the vessel, one interviewee was put to shame however. While he was condemning the people that clambered on board to loot the contents of the radio ship a tin of coffee slipped from under his coat for all to see.

At the time, as a boy of just 15, I was extremely annoyed with the Belgian government for bringing in Marine Offences legislation, rather than put their own broadcasting house in order. Later I understood that such is the way of politicians and therefore they should never be trusted. Shortly afterwards Prime Minister Théo Lefèvre spent some time in Duinbergen, just a few miles from where the Uilenspiegel ran aground. Whether he went to visit the wreck in the thick snow, as many of his countrymen did, I do not know. A few days after the radio vessel ran ashore the Big Freeze had set in with major snowfalls, temperatures that reached minus 20 and no frost-free nights until March 5th 1963. In spite of the Siberian weather I did get to give the ever lip-licking Prime Minister (he had a nervous tick) the evil eye though when, during the Xmas holidays, he dropped his son off at the Xaverian school in Heist for extra Algebra-tutoring by Brother Victor. Apparently the boy was just as hopeless at it as myself.

DANGEROUS

TOURIST ATTRACTION

Over

the years the Uilenspiegel, having found her final resting place on

the beach, with the bow pointing towards Antwerp, slipped ever deeper

in the sand. For a long time the wreck remained a popular tourist

attraction. Many Flemish day trippers and German holiday makers

flocked to the remains of the legendary pirate. One afternoon in the mid 70’s also RNI-colleague Andy Archer and myself walked to the stricken wreck of the Uilenspiegel. Later a

young German tourist broke his back as he fell from the hulk. The

town council in Sluis subsequently decided to have the upper

structure blown up. Afterwards parts of the concrete keel could still

be seen sticking out of the sand at very low tide. In 2001 growing

concerns over safety made the authorities incorporate the debris of

the Uilenspiegel keel into a new breakwater. And so the former radio

ship, that was wrecked by the power of the waves, became part of the

coastal defences to keep in check these same waves, now egged on by global

warming.

FISHY

ROYAL PRIVILEGE

Few are aware that the ‘Nele’, Uilenspiegel’s very small tender, went on to make history of her own. In 1963 Victor Depaepe, who lived in Zeebrugge, found a document in the city archives at Bruges which was signed by King Charles II and had been forgotten for some 300 years. After his father had been beheaded, and since Cromwell was in power in Britain, the then Prince Charles took up residence in several European cities, each time until the money ran out or politics forced him to move on. From 1655 he also spent time in Bruges. Charles was running up large bills in the town and did not have the means to pay them. That’s when he had an ‘Eternal Privilege’ drawn up. This granted 50 Bruges fishermen -appointed by the town- the everlasting right to fish in British territorial waters.

In 1963 the ‘Nele’ was renamed ‘King Charles II’ and Victor Depaepe –whom everyone called Fikken Poape- set sail and soon started fishing just a mile from the English coast. This was what the maritime inspectors had been waiting for. Sea fishery officers came on board and confiscated the catch. The Royal Privilege was said to be no longer valid. But Victor Depaepe (1922-1997) was not prosecuted and hence did not get his day in court, which he had hoped and prepared for.

In 1963 the ‘Nele’ was renamed ‘King Charles II’ and Victor Depaepe –whom everyone called Fikken Poape- set sail and soon started fishing just a mile from the English coast. This was what the maritime inspectors had been waiting for. Sea fishery officers came on board and confiscated the catch. The Royal Privilege was said to be no longer valid. But Victor Depaepe (1922-1997) was not prosecuted and hence did not get his day in court, which he had hoped and prepared for.

Many years later when the Public Record Office in London released documents relating to the Depaepe-incident, here too unsavoury cover-up politics transpired. Lawyers for the British Minister of Agriculture had advised to avoid a court case against Victor Depaepe because it would prove that the privilege issued by Charles II was still very much legally valid. So it proves that the legitimate aspirations of the people behind both the Uilenspiegel and the Nele largely foundered on the deviousness of politicians.

More of AJ's radio- and other anecdotes.

More of AJ's radio- and other anecdotes.

I remember you telling us the sad Radio Uilenspiegel story on your excellent Northsea goes DX program on Sunday mornings on RNI 6205/6210 Shortwave. I had a nice Grundig Yacht Boy radio with the 49 and 41 metre band on it and the reception of RNI was great.

ReplyDeleteStill brings a lump in the throat.

ReplyDeleteNSGdx used to love it was at school and I recorded every week.

Sad to say the old radiogram is a tool cupboard now in the shed

We must be mad to let all that dedication go!